Analytics have grown in importance over the past few decades, and the capabilities available through recent technological innovations are amazing. Business investments in analytical solutions are ever-increasing—denoting the strategic importance placed in these solutions. Yet the most difficult aspect to realizing success with analytics has been, and continues to be, the organizational challenges getting those stakeholders most likely to benefit to embrace an innovative mindset.

People talk about building a culture that enables innovation. However, most people still exhibit ideas and actions that keep them grounded in “how things have always been done.” Conversely, some look to invest, but want to take a completely hands-off approach in how analytical tools will be leveraged. In either case, the real hurdle to succeeding with analytics is not the technology but the culture of the organization.

Build it and They Might Not Come

Early in my career, I was fascinated by the possibilities available by using data and analytic techniques to solve business problems (and still am!). One of the first big problems I tackled involved using predictive capabilities to support and prioritize marketing efforts. Back in 1995, a colleague (John Crites) introduced me to a relatively new analytic technique called “neural network modeling.”

We worked together to develop segmentation plans and predictive targeting capabilities using this and other analytic methods. Having become very enamored with our approach, which was very leading edge in the mid-90s, we presented our findings to our boss, the vice president of marketing.

Armed with a statistically valid and innovative approach to marketing, detailed data to back up our findings, and an abundance of youthful enthusiasm, we made our case. Our boss listened to our pitch, then delivered a line I’ll always remember, “Guys, that math of yours is all fine and good, but me … I market from the gut.” He proceeded to deliver a dissertation on how marketing is something a person feels and is subjective rather than an objective science.

Admittedly deterred, we nevertheless plodded ahead and continued to demonstrate how much more effective our approach was than the current “shotgun” sequential direct marketing tactics. After some time and a lot of convincing, we were given a pilot to test our approach. When the results came in, we were ecstatic to see that we had far exceeded existing campaigns. Even our boss was impressed—so impressed, in fact, that he said, “Let’s continue and use this approach to contact everyone.”

Needless to say, our results diminished as we targeted the remaining candidates—for the exact reason we prioritized contacts in the first place. Despite our attempts, which turned out to be in vain, to explain how predictive targeting works by prioritizing our efforts, we eventually came to understand that a semi-monopoly in a regulated industry has little need to use advanced analytics to prioritize leads. That’s when I realized we would never be successful leveraging our newfound analytic innovations at that company. It’s also when I decided to quit that job and pursue a consulting career that allowed me to work with companies where real analytical opportunities exist.

You Get the Behavior You Reward

What I failed to realize back then, but have never forgotten since, is that you get the behavior you reward. The company expressed interest in applying innovative, analytically-based science to its marketing strategy. It supported a pilot and was genuinely impressed with the results. At the end of the day, however, executives were not incentivized to implement those capabilities. Therefore, as much as they talked about being converts by embracing an analytic mindset, they were never truly interested in supporting an analytic culture.

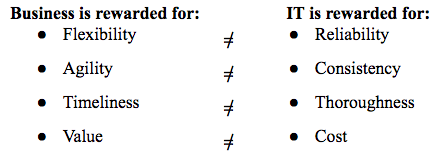

Unfortunately, this is not an isolated scenario. It’s still common today. The best example is the chasm between most business and IT organizations. These groups have diametrically opposed reward systems. To build and expand a culture of continuous innovation requires them to work together.

Neither of these groups are wrong, and the goals they have are all valid. What’s evident, however, is that these goals, on the surface, are incompatible across the business/IT divide. I cannot count how many times I’ve heard business users proclaim, “IT doesn’t understand the business” or “IT is too slow and bureaucratic to support our needs.” Of course, these are the same people who scream if a system shuts down unexpectedly, there’s data inconsistency, or IT didn’t understand some ill-conceived requirement and interpret what business users actually wanted (rather than what they said they wanted).

Likewise, I’ve listened to IT staff complain that too many users are doing too many things, and if they had fewer of both, the system would run so much better—never mind that the whole reason for IT in the first place is to enable more business users to get more value and results from the company’s technology investments.

What happens when both groups take their individualistic and myopic view of innovation? IT puts up roadblocks, forces excessive governance, and follows requirements exactly as they are written rather than collaborating. Business users, in turn, grow frustrated, build data silos and shadow IT organizations, or reach out to third parties for “hosted” solutions. In the end, neither side wins. The company will continue to invest in innovative technologies, but its culture won’t allow teams to realize the true potential of these investments.

Developing an Organizational Culture to Maximize Your Analytical Initiatives

In my experience, many people talk about collaborative analytical innovation yet exhibit none of the enthusiasm and discipline required to bridge the organizational gap between the business and IT. Instead, some choose to follow marketing hype and ambiguity by thinking that someone else has the “best practice” for what they are looking to do. The result? Many companies let external third parties develop, and ultimately own, the data and analytics that drive organizational automation. The external vendor gets smarter, but the internal associates get further removed from understanding their operating environment and how best to apply analytics to support their business.

My latest white paper provides a five-step strategy to build and maintain a culture of innovation that considers these two seemingly incompatible organization partners. These strategies address the business need for innovation and the ability to “fail fast” while also realizing that IT excels at making sure the deployment and reliability of technologies are fully optimized.

Ultimately, the paper provides a proven methodology to create a win/win process as well as develop a data and technological infrastructure that allows the talented employees across the company to do what they do best and achieve the outcomes they need. More importantly, it establishes an environment where everyone’s efforts are suitably rewarded and collaboration is encouraged. There are many great solutions and techniques that can be leveraged by third parties. However, this methodology presupposes that the analytical leadership will come from within your organization—not outside of it. Hopefully these strategies will help you overcome objectives the next time an executive tells you to “market from the gut.”

Tom Casey is Executive Account Director for Teradata. He has nearly 25 years of experience working with, designing solutions around, and helping global customers make analytics actionable. As a data analyst, Tom has successfully implemented the use of statistics to better segment and target customers in support of major corporate programs. He’s a featured speaker at conferences, author of several papers, and has a solid track record delivering enterprise-scale analytical solutions.

View all posts by Tom Casey